Glimmers of sunshine on budget day, but the clouds have gathered since November's Autumn Statement.

Photo: HM Treasury (Flickr) / CC BY

The March 2016 budge has been and gone. GDP growth forecasts have been downgraded, the deficit will persist longer than the Chancellor expected, and the debt-to-GDP ratio has still not peaked yet.

George Osborne set out as Chancellor all the way back in June 2010's "emergency" budget to rescue the British economy from a Greek-style debt crisis selloff of government bonds.

He set himself three golden rules, for people to judge his performance.

1.) He hoped to cap welfare spending over the 2010-15 Parliament. He failed.

2.) He hoped to get the debt-to-GDP ratio falling. He's still not achieved this yet.

3.) He hoped to achieve a budget surplus by the end of the Parliament. That was supposed to happen in 2015. Now it's been extended out, to the 2019-20 financial year. Let's see how that goes.

As it stands, he hasn't quite lived up to his own standards. If he fails to achieve a budget surplus by 2020, Mr Osborne's alleged aspirations for higher office will be blown out of the water.

There were some rays of sunshine, amidst the rhetoric and barrage of statistics yesterday. The ONS announced that unemployment remained at a 10yr low of 5.1%, whilst average earnings rose to 2.2% in January (well ahead of inflation). The so-called feel-good factor of real wage growth remains in place, for now at least.

Wage growth since the financial crisis. Is the recent recovery too little too late?

Source: ONS/Timetric

If the feel-good factor is supposedly upon us, why was the budget so gloomy?

Simple: the economic growth and productivity gains which the Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR) pencilled in, back in 2010, failed to materialise. The government's having to cut further into the welfare state to balance the books.

Government ministers are often heard justifying the cuts to public spending, by using the analogy of a spendthrift household. The idea is that you must live within your means, or you max out the credit card, and no one will lend to you.

Except the UK government isn't a household. A household in work can get a rough idea how much it can earn in a year, to keep things running smoothly. The Treasury can only guess at how much tax revenue it can generate.

Spending plans are all very well, but if productivity is weak, wages fail to take off. Wages help fill the coffers, and if they're subdued tax receipts will lower. The cuts will be made, but the tax base will be too low for the cuts to be enough to balance the books.

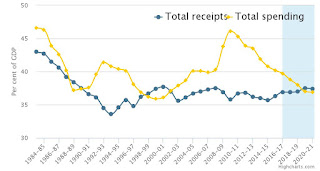

The gap is forecast to close, but it'll come half a decade late than originally planned

Source: OBR

Speaking to me before Mr Osborne announced the OBR's economic forecasts at the dispatch box, economist David Blanchflower told me he expected growth to be "downgraded but still too optimistic".

As it turned out, economic growth will be fairly steady. We were told to expect average growth of 2.1% a year by 2020. It's slightly below the "long-run" growth rate economists use to talk about, of about 2.7%.

The forecasts predicted that unemployment would bottom out and rise slightly, to 5.3% by 2020. This would imply that the surge in job creation over the last 4yrs will peter out somewhat, despite the steadily-growing economy.

In other words, we are being told to expect future growth to be the result of higher productivity, as opposed to an increase in the supply of labour.

US Federal Reserve and Bank of England refrain from rate hikes

This is news that came in two parts, during the day. The Federal Reserve announced it intended to avoid hiking rates in March. The Fed notoriously hiked rates back in December 2015, and chaos ensued.

Now the Bank of England has announced rates will remain at 7yr lows. The OBR's forecasts implies rates might get cut below 0.5% in the next two years, if conditions continue to deteriorate deteriorate

Japan's central bank cut interests rates into negative territory, and the ECB followed suit. It cut its deposit rate even further into negative territory this month. Global stock markets tumbled earlier this year, over fears negative rates will hit the margins of financial institutions.

The current so-called emerging market crisis is easily explained. When the Fed electronically created billions of Dollars, over three sucessive rounds of QE, they were able to keep a lid on the Dollar. Commodities like Oil, Gold and Silver rocketed until 2011.

When new Fed chair Janet Yellen announced a taper of QE in 2013, emerging market currencies peaked, and began to tumble, and commodities along with them, as the Dollar began to rally.

Even the hint of a rate hike, plus a slowing Chinese economy has sent Oil prices down to 12yr lows.

No comments:

Post a Comment